Dylan Huw: Amser / cyd-weithredu

Writing commission by Dylan Huw

Amser / cyd-weithredu

Dylan Huw

mae amser chwarae yma

amser chwarae fyny

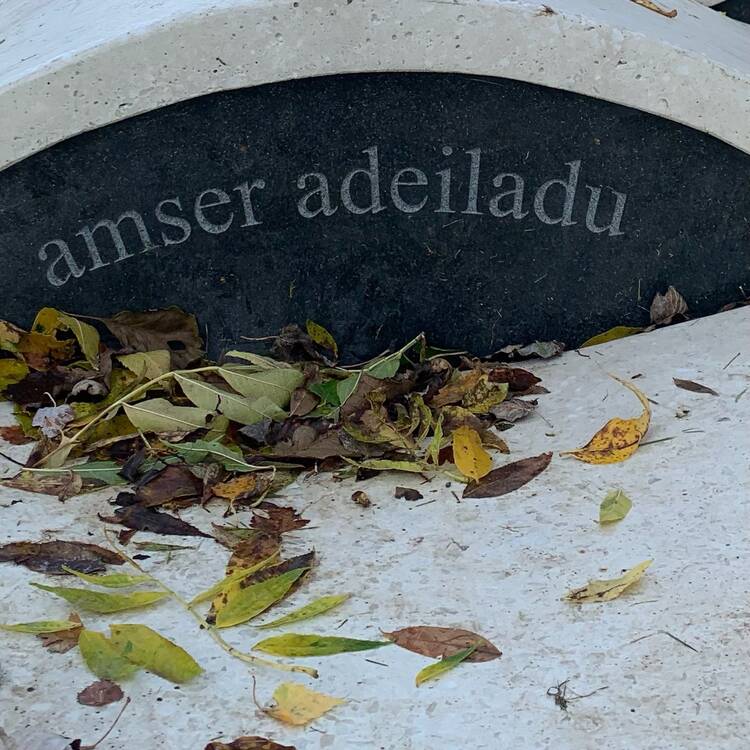

amser adeiladu.

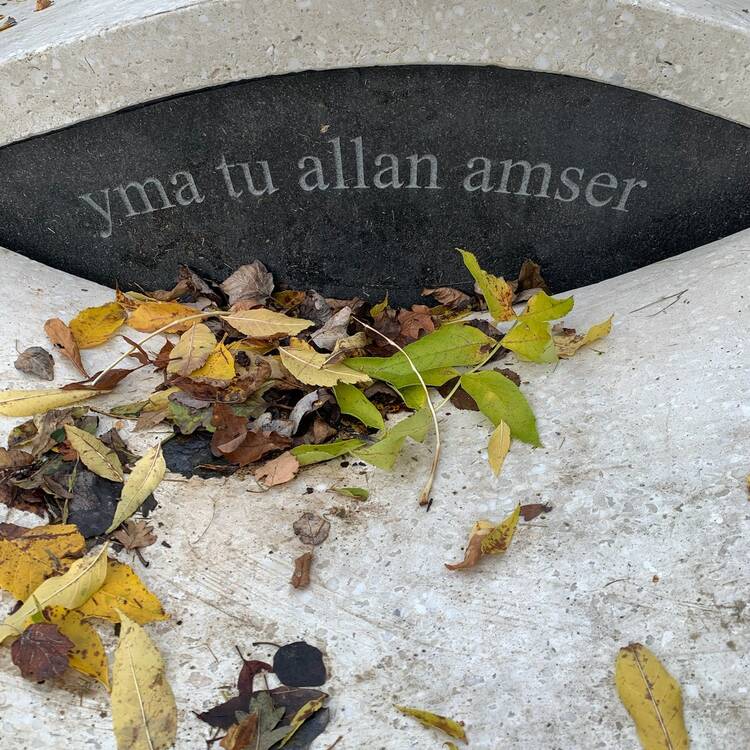

yma tu allan i amser

mae’n amser

cyd-weithredu.

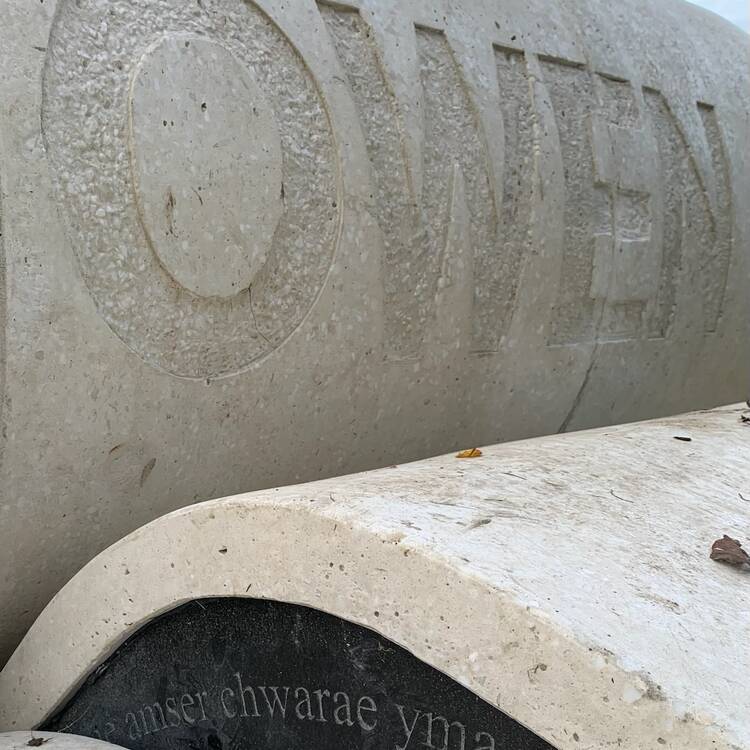

Robert Owen has meant many things to people the world over, but nowhere to the same extent as Newtown, where he was born 251 years ago. Aspects of the narrative surrounding his writings and experiments, however, have historically been elided in service of the kind of simplified hero narratives by which we like to remember those who are perceived to have made some positive difference to how we live. It has come to feel increasingly imperative to acknowledge Owen’s failure to confront the great ethical issue of his day, the abolition of slavery, and to include as part of the wider narrative of his work and how we memorialise it the central role played by enslaved people in the USA, Brazil and Caribbean in creating the fortune that enabled him to enact his experiments at New Lanark and elsewhere.

How to root these difficult conversations in the local, in today’s Newtown, while staying true to the town’s pride in Owen’s considerable historical significance? The tensions evoked by these imperatives, to right the omissions of previously popularised narratives about Owen and his legacy, are what felt rare, and potentially generative, about the challenge set by Oriel Davies in inviting me to contribute short pieces of text, alongside Sadia Pineda Hameed, to Howard Bowcott’s sculpture erected in Newtown as part of the 250th anniversary commemorations of Owen’s birth. Perhaps ‘commemoration’ is an insufficient word in this instance; while this particular sculpture would certainly be part of the wider celebrations of the influential social reformer and philanthropist, it would play no part in any lionisation. It would instead attend specifically to the complexities at play in how we pay tribute to figures whose flaws or wrongdoings or evils should have never been invisibilised to allow us to remember more comfortably. Bowcott’s sculpture, including the words engraved on it, is in this sense a work explicitly concerned with what it means to use artistic means to memorialise at all; a monument which problematises the impulse to monumentalise. Finding ways of containing these tensions in just a few short phrases of text, as part of a work which is also intended to become part of the fabric of a town’s everyday architecture — a space for leisure, play, contemplation, relaxation — was no easy task.

Some answers (or, at least, more, useful, questions) as to how to adequately meet these challenges lay in Owen’s writing, and that of other thinkers, some of whose work is perhaps partly indebted to Owen. I was interested in foregrounding, through the prism of the question of Robert Owen’s legacy today, how perennially complicated and politically loaded are notions of play, and by extension freedom, in our contemporary as in Owen’s. Drawing on Owen’s seismic and enduring influence in the field of early-life education, I let the Welsh term for play-time, amser chwarae, and the multiple meanings and evocations that arise from the term (which could also mean time to play and, possibly, playing with time), lead. As I was commissioned to contribute specifically in Welsh, I was keen to take a playfully self-conscious approach to the language, or to language itself, by seizing upon the ambiguities evoked by double and triple meanings. For instance, I was interested in centring the cyd-weithred, that is, the dual meaning of the Welsh word for ‘co-operate’ (referring to Owen’s reputation as father of the co-operative movement) to mean both cooperation and something like co-actioning or ‘collective action.’ In so doing I hoped to evoke the spirit of protest and collective solidarity-making in conversations about how we ‘memorialise’ influential figures of the past.

In a text recently published by MARCH, Lital Khaikin illuminates some ways in which playgrounds themselves “are powerfully representative of the economic and psychic divides across race, gender, class, and physical mobility.” Khaikin draws specific attention to how the traumas of apartheid and military occupation make play an impossibility for children living in Palestine, in one example. If a world is unlivable, as ours is for so many, this is always rehearsed too in the spaces we designate for play. Khaikin writes:

Early play is life “testing” the world, creatures traversing the possible, exploring and confronting the void of the unknown, expectant with discovery. In this sense, play is also a flirtation with fear, creeping along the edges of a supernatural landscape that hovers delicately between safety and traumatic catastrophe. While its inconclusive nature calls for never quite touching upon one or another of these thresholds – always in between and not-yet – play disintegrates in the moment it touches upon catastrophe.

These disintegrations feel like an apt metaphor not only for the role of play in wider society but for how complex human legacies cannot and should not lie dormant, untroubled by evolving social norms. In describing his work at New Lanark as “the most important experiment for the happiness of the human race that has yet been instituted in any part of the world”, what factors limited Owen’s perception of the scope of challenges actually faced by the “human race” that we can now understand more fully? Thinking about how zones between the adult and child worlds, such as playgrounds, often can’t help but be interrupted by ubiquitous societal forces has been instructive in how I think about Owen’s legacy in our present day, to grapple with these questions and others.

These kinds of nuanced negotiations around contemporary dynamics which many assume to be uncomplicated usually happen a million miles away from anniversary celebrations afforded figures like Robert Owen. But there is no way of assessing a legacy such as his without considering how the areas in which he worked are made complex in all kinds of ways contingent on shifting spatial and temporal realities. I hoped with my brief text to activate a sense of history as always in a state of being reconsidered and reconstructed, and to emphasise that play, pleasure and collective action are always intertwined, always in a state of complex negotiation. By referring to a place outside of time (yma tu allan i amser), I wanted to acknowledge that the site of the sculpture is itself intended as a meeting point and a place for public wandering, not merely as an artwork for contemplation. Personally, I hope that despite — no, because of — the sensitive questions that Bowcott’s sculpture, and Sadia’s words and mine, aims to grapple with, about how legacies are formed and popular memory shaped, and how we should always be casting a critical eye upon the ‘great men’ of history in order to renew our understanding of them, it becomes a fixture of the town’s everyday life. Let’s meet by the Robert Owen sculpture, down by the skate park: to play, to laze around, to put the world to rights.