Georgia Ruth: Find our way back to the week of pines? - part 2

A blog exploring responses to works from CELF

Perhaps because of the terrifying images of the wildfires burning through Southern California, I become preoccupied with the idea of tracking down the Montgomeryshire trees from Geoff Charles' photos.

Everything is so fragile, so vulnerable. I get upset thinking that the planting might have been pointless; that W H Rees and the others put on their best hats and coats, dug their fingers deep into the earth to lay roots, for nothing. And I imagine other hands, too; planting saplings into Californian soil, building houses…

But it's been snowing in mid Wales, and I'm heavily pregnant. So, I default to the modern way of doing things.

First, I try to find the Aberbechan poplar.

I always think of Clarice Cliff tea sets when I imagine poplars; in her world, they’re never alone, always standing in melancholy formation with at least one mate.

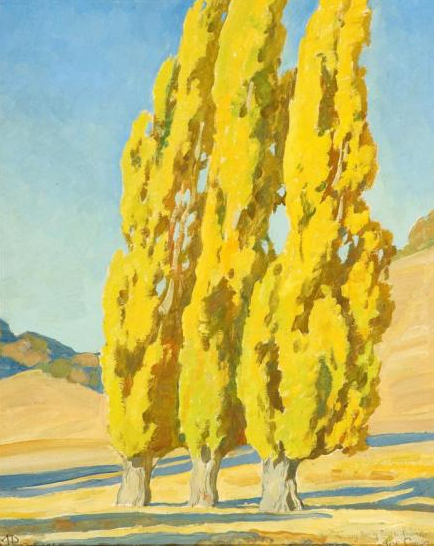

Or there’s Maynard Dixon: who painted the poplar trees in his beloved Carson, Nevada like yellow plumes of smoke.

In virtual Mid-Wales, I spend an hour aimlessly roaming along the B4389 on Street View, searching for something that looks like the forestry in the photograph of Aberbechan. But however many times I scour the surrounding fields, I find nothing. Perhaps I’m on the wrong road. (Oddly, it’s eternally summer on Street View – with no trace of the snow or frost that I can see clearly from my window…)

I type ‘Bechan Forest’ into Google. All I find is a luxury holiday cottage retreat offering pine lodges and cabins with hot tubs. The website talks about ancient woodland and rolling pastures. I find some pictures. The cabins have English names like 'The Kingfisher'. Sure enough, they're flanked by trees. Maybe one of them is the poplar, I think. But, of course, there's no way of knowing; it’s like looking for a pine needle in a haystack.

I turn my attention to the Tasmanian eucalyptus. Ffridd Mathrafal is much easier to find remotely. Today, it’s under the care of the Woodland Trust and you can visit any time.

I dig up an amazing document on the history of the forest, published in 1952 (just one year before the ‘Montgomeryshire Forest Adventure’ began.)

It gives me a detailed geological analysis of the Mathrafal soil.

"The underlying rock formations are the Bala beds of Ordovician shales and Silurian grit."

(I love how that sounds. Silurian grit. Like a personality trait worth having. ‘She’s got Silurian grit, that one.’)

It tells me about the predominating native species: Oak, ash, hazel, birch, alder; bramble, wild strawberry, bluebell, rose bay willow herb, dog’s mercury, wood sorrel, ground ivy, honeysuckle and foxglove.

Then lists the trees that have been planted:

Scots pine, Corsican pine, European larch, Japanese larch, Douglas fir, Norway spruce, Sitka spruce, Thuya, Tsuga, Ash, Sycamore, Red oak.

Later, it reports on how they've all been getting on, some better than others. In 1949, someone writes, the "small Japanese larch belt had failed completely owing to the plants arriving in poor condition." The Norway spruce, however, was doing brilliantly.

But, because this account ends 12 months before Mr Rees stands in his trench coat for the camera and plants the eucalyptus into the soil, that particular tree is missing from this record.

Street View won’t let me go into the forest and so I have no way of finding it. I resolve to go there – in person – once the baby's born. Even if I don't find the eucalyptus, there are two iron age settlements that I’d love to see.

Almost without thinking, I return to my phone.

On BBC News I read that climate change – and the “rapid swings between dry and wet conditions” – is responsible for creating the “tinder-dry” shrubs and grasses that have made Los Angeles so vulnerable to burning.

On Instagram, I watch footage of firefighters in Pacific Palisades rushing to save photo albums and keepsakes (including a huge antique grandfather clock) from a burning home. “Just trying to save some photos,” one of them says to camera, setting the albums down safely on a bench, before returning to the flames.

More than 100,000 people have been displaced. Sixteen people have died.

A tweet, originally posted before the wildfires, starts to circulate again.

“climate change will manifest as a series of disasters viewed through phones with footage that gets closer and closer to where you live until you’re the one filming it.”

In 1952, the main risk to Ffridd Mathrafal was fire.

"The greatest danger is in the spring and autumn when the weather is dry and the bracken is highly inflammable."

You can see the bracken leaves surrounding W H Rees' boots in Geoff Charles’ photo.

References

Clarice Cliff, POPLAR, VASE (1932), Available from: https://andrew-muir.com/items/... [Accessed 15 January 2025].

Maynard Dixon, Autumnal Poplars (1932), Available from: https://cdaartauction.com/auct... [Accessed 15 January 2025].